We all do it. We make assumptions all the time. About everything.

In genealogy, we make assumptions about our ancestors, although their worlds were far different than ours.

We make assumptions about the records. Beginners often assume there’s “no record” of an ancestor simply because they cannot find it–for any one of a myriad of reasons. A researcher might assume that absence of one kind of record means that related records are also lost. Experienced genealogists are not immune from the assumption disease, either.

The 1820 population census schedules of New Jersey are long gone. They were lost long before there was a National Archives. But are all 1820 census records for New Jersey lost? No.

The 1820 manufacturing census schedules for New Jersey did survive, and they are published on National Archives Microfilm Publication M279, Records of the 1820 Census of Manufactures, Roll 17. There are schedules for over 300 men and firms, and it’s great stuff.

Here’s the list of New Jersey marshals, types of industries, and manufacturers found in the 1820 manufacturing schedules. The schedules are arranged by county (although not in alphabetical order), but they are also arranged in numerical order. Before microfilming, National Archives staff arranged the records geographically according to the arrangement in the published Digest of Manufactures compiled from these records in the 1820s, and then by any discernible system employed by the marshals. This arrangement permits the searcher to compare the individual schedules with the marshals’ abstracts and the Digest of Manufacturers tabulations.

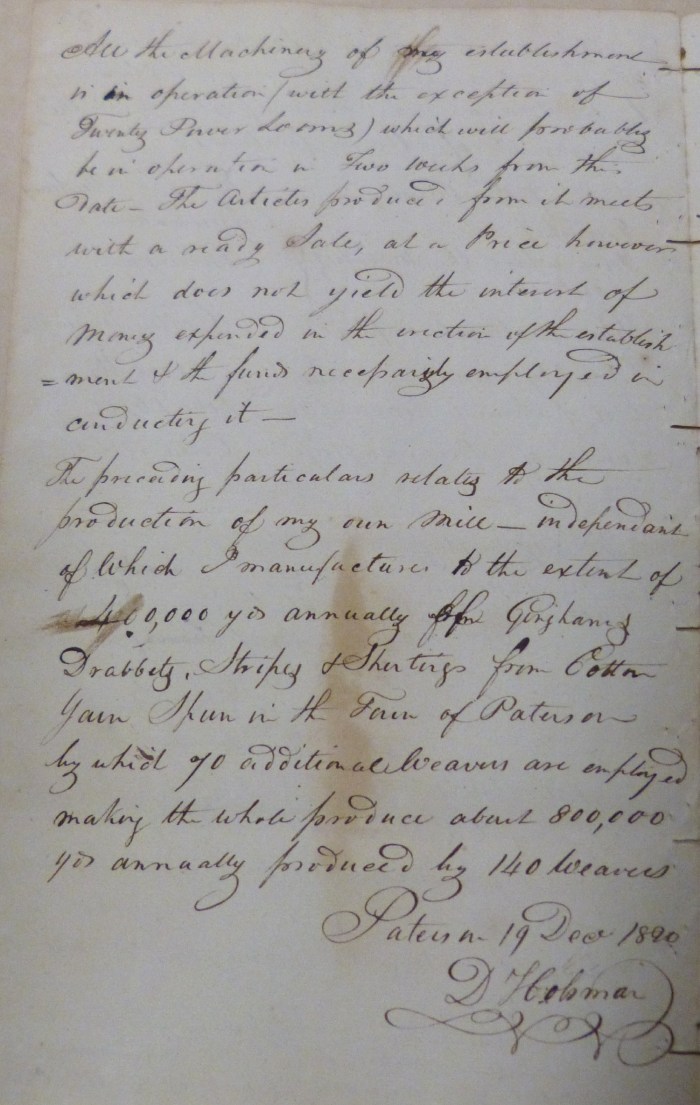

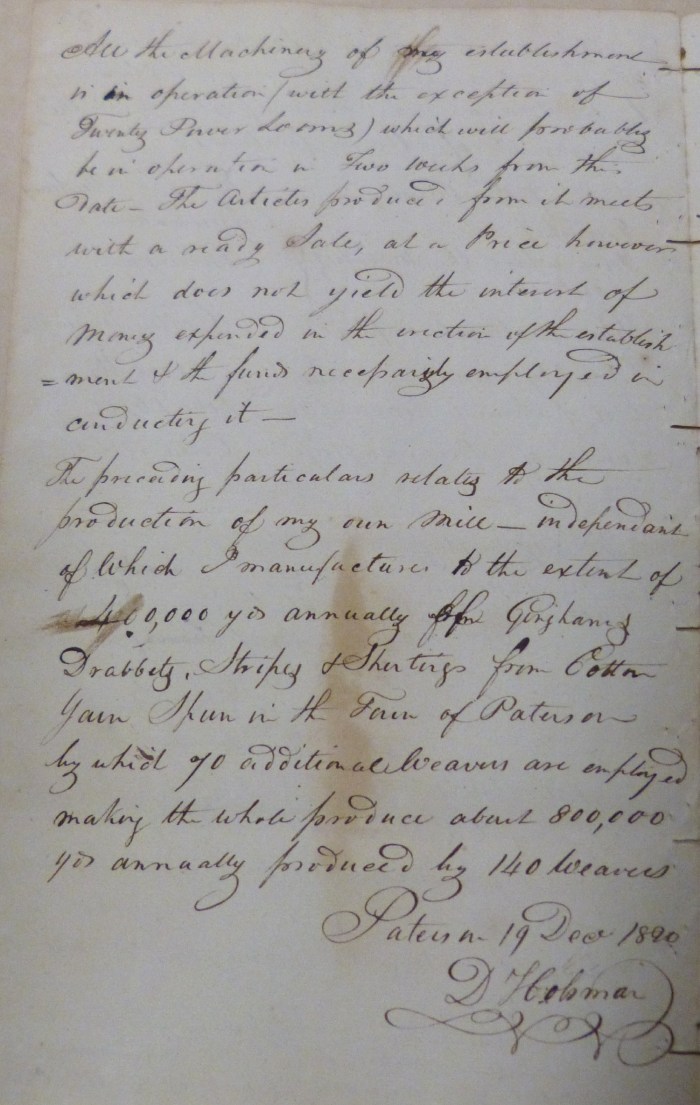

Certainly, the records show that these (presumed) heads of families lived in a particular geographic location in 1820. Better than that, however, the manufacturing census schedules document the economic underpinnings of these households and their communities. Here is the two page record for a cotton textile factory owned by D. Holsman in Paterson town, Aquacknonk township, Essex County (sorry for the blurriness in my photos). Page 1:

Page 2:

Some Assistant Marshals used pre-printed forms, as shown by this one dated at New York [City], December 1820, by J. Prall, part owner of the Rutgers Cotton Factory, also in Patterson [sic].

Great stuff. Both of the factories I’ve highlighted were “large” concerns, but there were also plenty of small shops included in the manufacturing schedules. If you had ancestors in New Jersey (or any state) in 1820, take a look at M279. You’ll be glad you did.

M279 Roll List:

1 – Maine and New Hampshire

2 – Massachusetts and Rhode Island

3 – Vermont

4 – Connecticut

5 -New York

6 – New York

7 – New York

8 – New York

9 – New York

10 – New York

11 – New York

12 – Pennsylvania

13 – Pennsylvania

14 – Pennsylvania

15 – Pennsylvania

16 – Maryland

17 – New Jersey, Delaware, and District of Columbia

18 – Virginia

19 – North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia

20 – Kentucky and Indiana

21 – Ohio

22 – Ohio

23 – Ohio

24 – Ohio

25 – Ohio

26 – Eastern District of Tennessee

27 – Western District of Tennessee, Illinois, and pages from the published Digest of Manufactures for Alabama, Louisiana, Missouri, Michigan, and Arkansas

I have not found M279 online. Viewing copies are available at the National Archives Building, Washington, DC, and at National Archives Regional Archives in Atlanta, Boston, Kansas City (Missouri), Philadelphia, and Riverside (California). It can also be found at libraries with large genealogical collections.

Here is an easily accessible copy of the descriptive pamphlet (DP) for M279, which also describes and identifies where manufacturing data embedded within the 1810 population census can be found.